Over the past two years curriculum and assessment have changed and developed more rapidly than I can remember; the emphasis on evidence informed practice is refreshing and brings clear rationale to the ‘why’ when individuals, faculties or whole schools introduce change. The drive to improve becomes purposeful and a collaboration when exploring the evidence together.

Curriculum and assessment cannot exist on their own, they form a symbiotic relationship that forms a clear Teaching and Learning strategy. This relies on both curriculum and assessment being well designed and integrated together to complement each other. The T&L Strategy then presents the potential for high quality teaching and learning; bring in the craft skills of the class teacher to execute the T&L Strategy and students will receive a high quality education.

- A high quality curriculum provides the classroom teacher with a logical Learning Journey to take their students on, but without assessment it is just a sequence of lessons with no way of informing the teacher how to teach responsively to the needs of the class.

- An assessment strategy provides the classroom teacher with a means of checking what students know, but without a strong curriculum the assessment is less informative and limits how responsive a teacher can be to the needs of the class.

Along with lots of reading and researching (see references at the end for many of these), the current recipe for constructing our curriculum and assessment strategy has included:

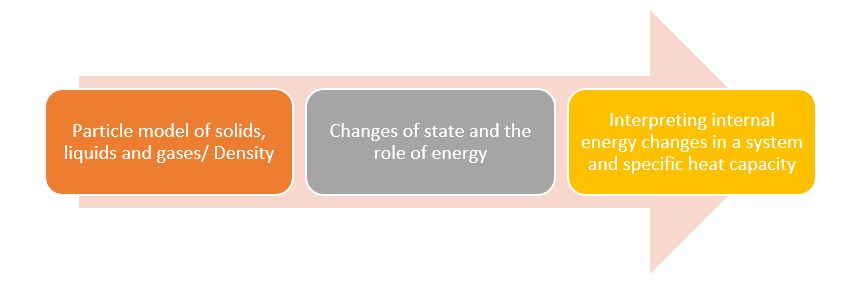

- Sequencing the concepts of the science curriculum into a logical Learning Journey of ‘building blocks’, considering the Threshold Concepts that underpin progression.

- Building a teaching order that ensures topics are regularly revisited and build upon, this involved a ‘spiral’ curriculum design that brings in space practice and helps teachers plan interleaving of concepts based on the needs of their class.

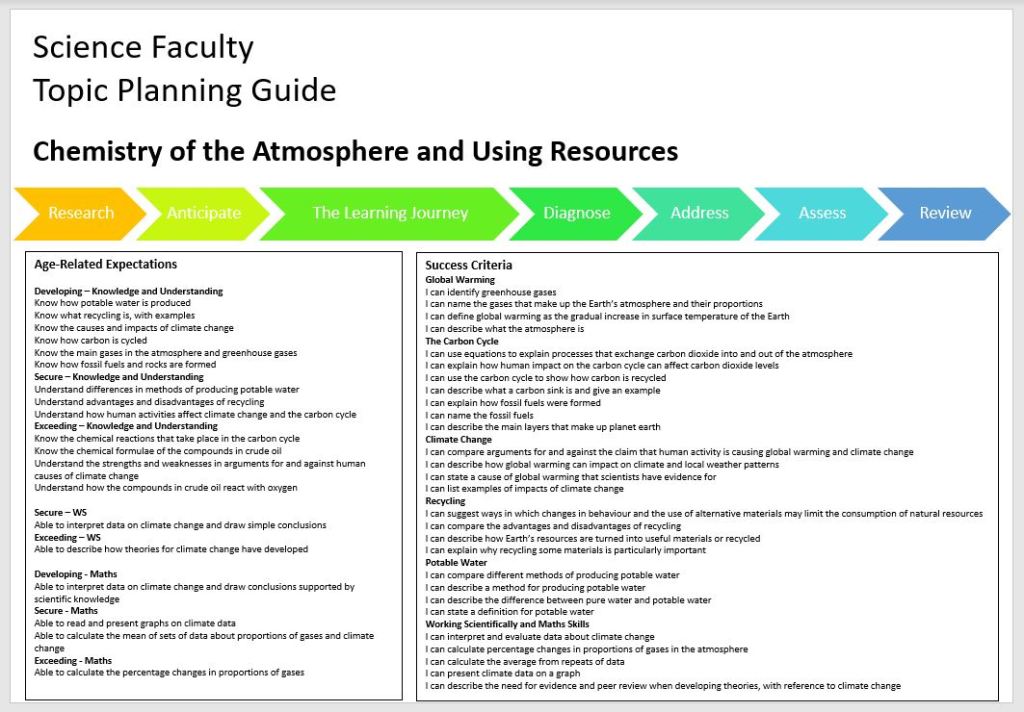

- Constructing clear age-related expectations and success criteria that students can be measured against.

- Introducing a whole school assessment strategy that enables all teachers to recognise how they use formative assessment to act responsively in the classroom; identify ‘hinge points’ in a topic for more in depth checking of understanding; and long term summative assessments to measure long term retention and plan for linking learning and finding the starting point for the next time the topic is taught.

- Developing pedagogy that will support delivery of the curriculum, much of it based upon Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction.

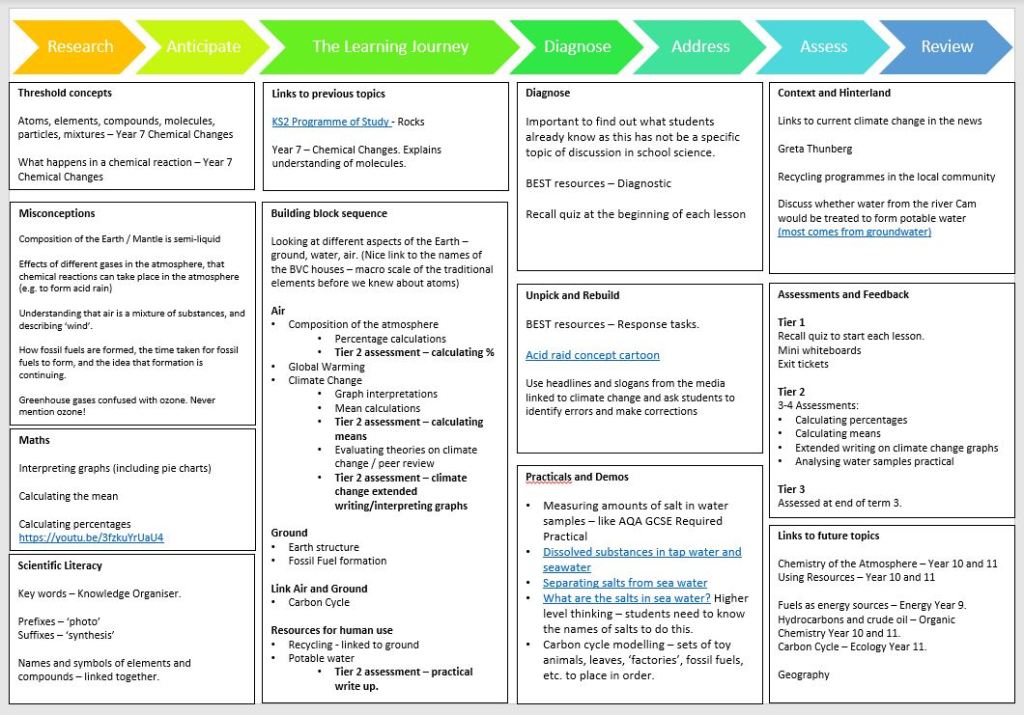

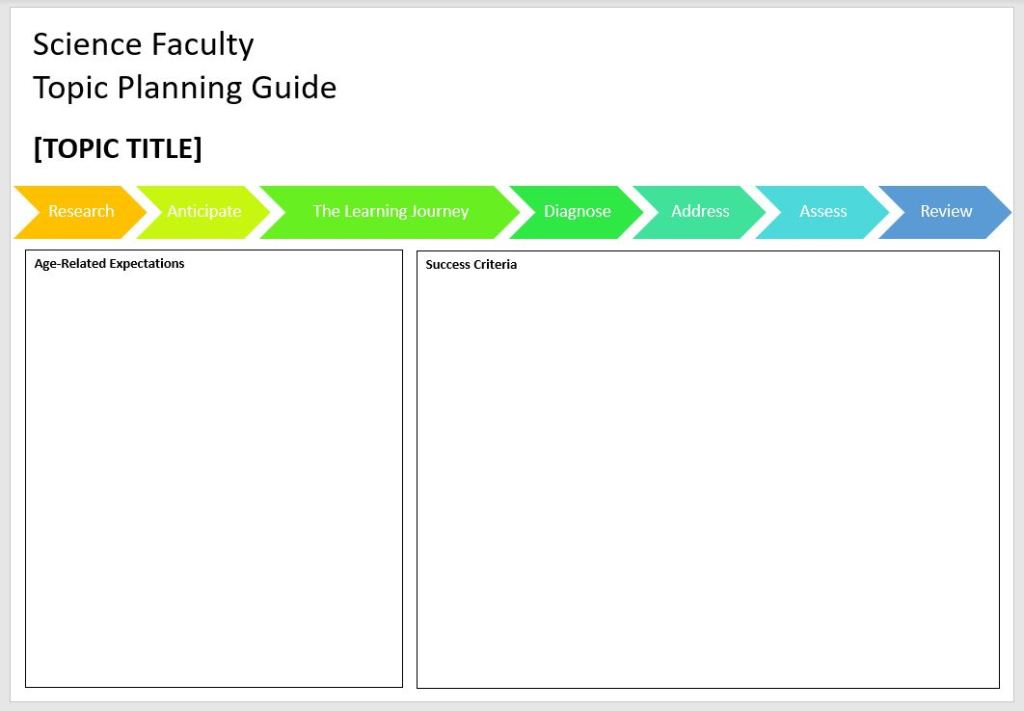

The most useful tool in helping begin bringing together our curriculum and assessment has been the RADAAR framework recently published by the EEF. RADAAR stands for: Research, Anticipate, Diagnose, Address, Assess and Review. This model provides a great foundation for enabling teachers to think and plan the sequence of learning and assessments for their class.

After first viewing this together as a faculty we noted how challenging this planning process is due to the amount of deep thinking required to be really cohesive, and also that non-specialists often lack the depth of knowledge to conduct this without much researching first. This encouraged us to develop our own version of the RADAAR framework that complemented our curriculum and assessment strategy. The aim being to produce a planning tool that does the ‘leg work’; the core thinking that goes into planning a topic, but leaving the autonomy for the class teacher to design lessons to meet the needs of their class; ensuring of suitable breadth and depth of knowledge, pace and appropriate activities to support learning.

Beginning with the age-related expectations (AREs) and success criteria we begin with the foundations of the topic. The AREs are what we are going to measure students knowledge, understanding and skills against; while the success criteria identify the types of things students will be able to do to in the pursuit of the knowledge, understanding and skills.

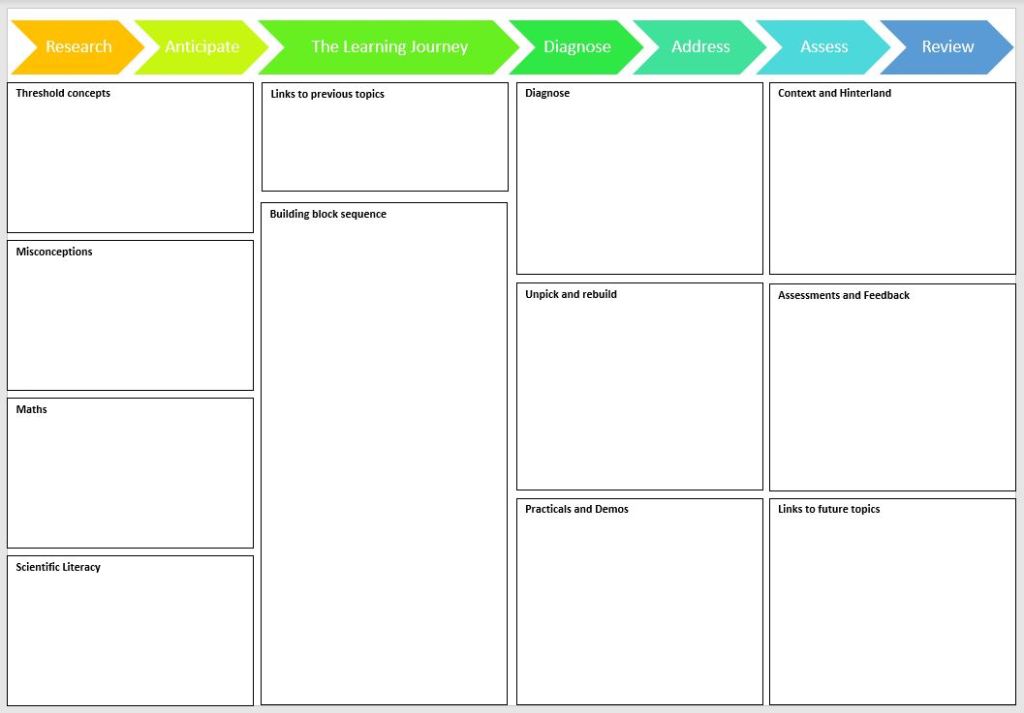

Next we continue in the ‘Research and Anticipate’ phases as we consider:

- Threshold Concepts – any specific concepts that are achieved in the topic that we consider are ‘portals’ to future learning, they are transformative, irreversible, integrative and troublesome. In some cases it may be that the threshold is in the future however students progress into a liminal state towards that threshold during this topic too.

- Misconceptions – what are students likely to arrive at the lesson thinking is true but actually it’s not. These may come from general learning through home life and the media; or due to some of the limitations of models at primary level (another interesting discussion!) Knowing this enables us to pre-empt and dispel these by paying particular attention to them and using teaching strategies to replace with correct science.

- Maths – What maths skills will be needed in this topic? How do our maths faculty teach it? This is to help us deliver consistently and enable students to transfer skills across the curriculum.

- Scientific Literacy – What tier 3 language will students encounter in this topic? What is the etymology of these terms? Knowing this helps us to make sure we teach these terms explicitly.

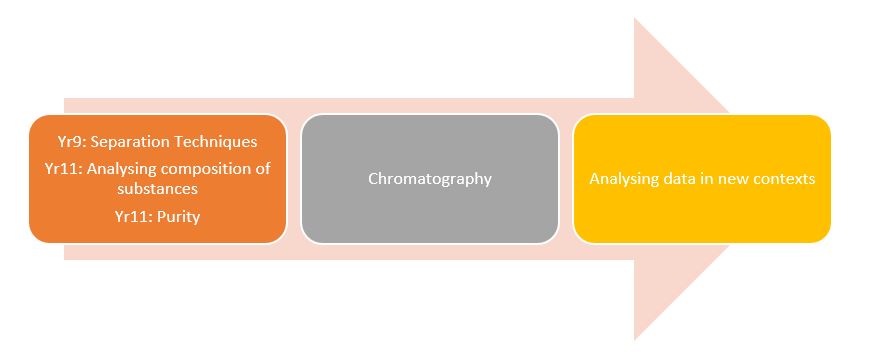

Our next phase is of our own inclusion (and suitably ruins the acronym RADAAR into the unpronounceable RALJDAAR…a dinosaur roar!) This focuses on the Learning Journey, and provides a key summary to support non-specialists to sequence the ‘building blocks’ effectively. There are two sections:

- Links to previous topics. To sign post the ‘baseline’ for students and things to formatively assess pre-topic and begin at an appropriate level of challenge.

- Learning Journey. A suggested order of concepts so that learning builds sequentially. We do not consider some of these orders to be gospel, but merely a suggestion for those who are unfamiliar with the topic.

- At this point it also important to draw attention to the bottom right corner box of Links to future topics. These are shared to enable staff to think about they will frame concepts to promote access to more complex ideas in the future without introducing misconceptions that need undoing in the future.

Diagnose and Address:

- The diagnose section identifies examples of resources that could be used to check for prior knowledge and misconceptions throughout the topic. The BEST resources for science have been invaluable here, along with concept cartoons too.

- Unpick and rebuild identifies suggestions on how to then tackle misunderstandings and misconceptions with classes, such as useful models and the ‘response’ BEST resources.

- Practicals and Demos really speaks for itself. A particularly useful section to support new staff and non-specialists in identifying practicals and demos that will support understanding the concepts of the topic.

- Context and Hinterland. Examples and ideas on how to bring the abstract science into concrete contexts to help students visualise and apply their learning. The Hinterland also provides scope for students to explore how classroom learning links to other ideas and real life scenarios.

Finally, Assess and Review. There are two sections to this phase, assessment and feedback. This section outlines ideas for ‘hinge point’ checks to ensure students have the underlying knowledge to access the next phase of learning. It also identifies opportunities for assessing skills such as extended writing and working scientifically. Feedback (not marking!) is encouraged to ensure students engage in improving their understanding after these assessment points, and that time consuming written comments do not go unaddressed when students do not know how to do so independently (see Feedback not Marking!)

The first planning guides are under trial this term with a view to finessing them and improving them to support us fully from September. One currently on trial is below.

References

- EEF Improving Secondary Science Report: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/tools/guidance-reports/improving-secondary-science/

- EEF RADAAR Framework introduced by Niki Kaiser: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/eef-blog-introducing-new-resources-for-sorting-out-scientific-misconception/

- KS1 and 2 Science Programmes of Study

- KS3 Science Programmes of Study

- KS4 Science Programmes of Study

- Range of Blogs, a weekly ‘Interesting Read’ for our faculty (Including Tom Sherrington, Teacher Toolkit, Adam Boxer, The Learning Scientists + more): https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1r6_nId32NRQ9GELci96U7FZ1TfVpQ_CKdY89SVt_Y8w/edit?usp=sharing

- Misconceptions in Primary Science – Michael Allen

- Making every science lesson count – Shaun Allison

- The ResearchEd Guide to Explicit and Direct Instruction – Adam Boxer

- The Feedback Pendulum – Michael Chiles

- The CRAFT of Assessment – Michael Chiles

- The ResearchEd Guide to Assessment – Sarah Donarski

- Responsive Teaching by Harry Fletcher-Wood

- Powerful Ideas of Science and How to Teach Them – Jasper Green

- Retrieval Practice by Kate Jones

- Teach Like a Champion – Doug Lemov

- Gallimaufry to Coherence – Mary Myatt

- High Challenge, Low Threat – Mary Myatt

- Rosenshine’s Principles in Action by Tom Sherrington

- Walk Thrus – Tom Sherrington and Oli Caviglioli